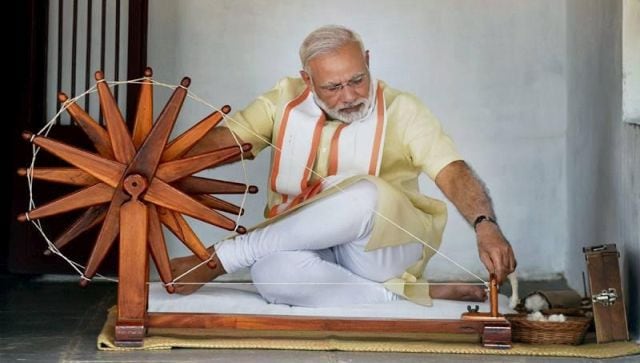

“This ‘khadi’ is not just a piece of cloth but also a weapon for those with self-respect…,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi on National Handloom Day on 7 August, urging people to adopt swadeshi. The handspun fabric was an integral part of our freedom struggle and while it was lost in time, it is now being cherished again.

For more than seven decades, the Indian flag that fluttered atop our government buildings and heritage structures has been made from khadi. During the freedom struggle, khadi was not just a textile but a non-violent tool picked by Mahatma Gandhi.

As India celebrates Gandhi Jayanti, here’s a brief history of khadi and its place in the world’s fastest-growing economy.

Gandhi’s tryst with khadi

The name khadi comes from the word ‘khaddar’ (meaning handspun in the subcontinent) and is part of India’s ancient handmade textile traditions that date back to 400 BC, according to the Greek historian Herodotus. By the late 17th Century, Indian fabrics were a rage in Europe. Soon they became the West’s envy and were banned by the British and French to reduce competition, according to an article in Vogue.

They were lost in time. But Gandhi brought the attention back to Indian textiles. Khadi, which is handwoven from handspun cotton, silk, or wool yarn, has now become synonymous with him.

When the Father of the Nation was leading the fight to boycott foreign clothes, he turned to hand-woven khadi. “Consume what you can produce,” he believed. The production of home-spun was the way forward, according to him.

It was in 1915 that Gandhi started his movement for khadi, hoping it would make the poor in the villages self-reliant and at the same time create employment. He considered spinning the wheel and producing home-spun cloth as the way to the economic liberation of the masses. It was the first step to ending dependency on the West, abandoning the use of foreign raw materials and becoming self-dependent… yes, atmanirbhar, as PM Modi says today.

The Mahatma realised early on that unemployment was plaguing India and saw the Khadi movement as an opportunity to create employment. During the dry season when farmers are idle, he thought spinning could keep them occupied and it required no capital. He also believed that the khadi industry could tap the potential of women and make them a part of India’s freedom struggle. “I swear by this form of swadeshi (khadi) because through it I can provide work to the semi-starved, semi-employed women of India. My idea is to get these women to spin yarn, and to clothe the people of India with khadi which will take the impoverished women out of it,” he said.

For him khadi was not just a cloth, he referred to it as a “Livery of Freedom”. In an article in The Hindu in 2010, Ragini Nayak, a former national general secretary of the National Students’ Union of India, wrote that Gandhiji emphasised that khadi “should be worn with values which are inseparable to it”.

“According to him, ‘The message of the spinning wheel is much wider than its circumference. Its message is one of simplicity, service of mankind, living so as not to hurt others, creating an indissoluble bond between the rich and the poor, capital and labour, the prince and the peasant.”

Interestingly, on 22 September 1921, Gandhi gave up his often khadi-made Gujarat attire and swapped it for a loin cloth. In a third-class train compartment when we has travelling from Madras (Chennai) to Madurai, when he pleaded for khadi, peasants told him, “We are too poor to buy khadi.”

He was wearing his vest, cap and full dhoti. It prompted the leader to change the way he dresses. “All the alterations I have made in my course of life have been effected by momentous occasions and they have been made after such a deep deliberation that I have hardly had to regret them. And I did them, as I could not help doing them. Such a radical alteration – in my dress – I effected in Madurai,” he said.

However, he did not want everyone to follow him. He wrote in the newspaper Navajivan: “I do not want either my co-workers or readers to adopt the loincloth. But I do wish that they should thoroughly realise the meaning of the boycott of foreign cloth and put forth their best effort to get it boycotted and to get khadi manufactured. I do wish that they may understand that swadeshi means everything.”

Khadi made the Swadeshi movement of 1905-06 possible. Patriotic Indians moved away from British textiles and products; spontaneous bonfires were seen across the country in which silks and laces from England were thrown.

Years later, in May 1915, Gandhi launched the Khadi movement from the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, Gujarat.

As hundreds and thousands of Indians started weaving their cloth, the mills of Lancashire, the cotton manufacturing hub of England, from where India was flooded with English goods, had to shut shop.

The fabric took the freedom movement to the masses and the villages. The charkha became a symbol of nationalism so much so that the original design of the tricolour featured the spinning wheel, as suggested by Gandhi.

Khadi in post-Independent India

The Khadi movement led to the creation of one of the biggest cooperatives in the world. The Indian government institutionalised the khadi industry by establishing the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) through an Act of Parliament in 1957. It aimed at providing employment and creating more opportunities in rural India. The KVIC supplied raw materials to producers, promoted research in production techniques, ensure quality control of products and promoted their sales and marketing.

But under Nehru, the focus was on industrial and mechanical production and khadi along with Indian handloom took a backseat. The country’s textile policy did not back handlooms even when it provided the second-largest source of rural employment after agriculture. Decades after independence, the powerloom sector saw a boom.

Synthetic fabrics entered the market further hurting handloom weavers and by the 1980s polyester became popular. Khadi became nothing more than a uniform of sorts of politicians.

Even today, powerlooms account for 60 per cent of cloth production in the country, while the share of handlooms is 15 per cent, reports Scroll, quoting the textile ministry reports.

Khadi back in the spotlight

The Modi-led government, with its vision for Atmanarbhar Bharat, put the focus back on Indian handloom. A year after the PM came to power, the National Handloom Day was established with the first celebration taking place on 7 August 2015. The date was picked as a tribute to the Swadeshi movement, which started on 7 August 1905 and promoted indigenous industries.

“After independence, much importance was not given to strengthening the cloth industry (Khadi), which was so strong during the last century…the situation was that it was left to die…people who wore Khadi were looked upon with inferiority complex…,” PM Modi said. But he is aiming to change that now.

In the past nine years, khadi has found a place for itself in the fashion industry with brands like the Aditya Birla Group and Raymond launching their collection of khadi wear. Models dressed in the fabric are walking the ramp as designers are innovating with the fabric.

“In the past 9 years, Khadi production has increased by three times and sales of khadi clothes also increased by 5 times. The handloom business turnover has increased from around Rs 30,000 crore to over Rs 1,30,000 crore and the demand for Khadi clothes increasing in foreign countries,” Modi said at this year’s National Handloom Day.

Seventy-six after independence, khadi is cool again. And we might have yet another man from Gujarat to thank.

With inputs from agencies

from Firstpost India Latest News https://ift.tt/pRHyc08

0 Comments