Political scientist Milan Vaishnav in his book, When Crime Pays, provides an engaging account of the sinister intertwining of politics and criminality. And, in his vivid account of this phenomenon, Bihar finds an important mention. With ‘bahubalis‘ who have held the heft of dictating the terms of politics, Bihar for long has been defined by its bad law and order situation. So, when a former top cop of such a state decides to write a memoir, the first anticipation would have been that it will spill some beans over this nexus.

However, when that top cop happens to be Bihar’s former Director General of Police (DGP) Abhayanand — a man of great ideas who is known for bringing Bihar out of lawlessness often defined as ‘Jungle Raj’ — the subtext of the memoir was bound to be law, rather than lawlessness, with the title of the memoir aptly being ‘unbounded’.

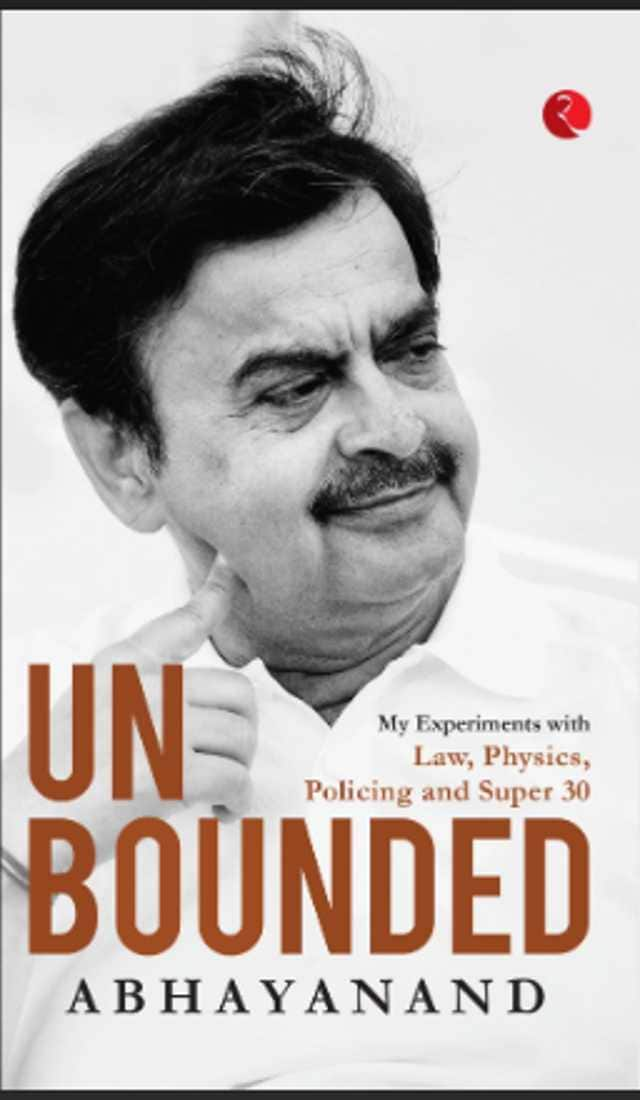

Abhayanand’s recently published memoir, Unbounded: My Experiments With Law Physics Policing And Super 30, is not just a memoir of a top cop, at least in its tone and language. It is a lively narration by a man on a mission who believes in the power of law rather than the force of ‘lathi’ in maintaining law and order.

It is an interesting account of a teacher whose infectious hope in education bringing in incremental but phenomenal change is perplexing. It is puzzling how someone part of the police force dealing with crime and criminals, manages to keep cynicism at the farthest bay.

The book is a fascinating account of his role as an Indian Police Service (IPS) officer and also touches upon his experiment with teaching and coaching underprivileged students to prepare them for one of the toughest competitive exams to enter India’s most prestigious engineering college — Indian Institute of Technology (IIT).

However, it is his insights and conclusions on the anatomy of crime and lawlessness in his state that forms the most compelling part of the entire narrative.

For Abhayanand “crime is essentially an economic activity” and in the book, he put forward a forceful and interesting argument to support his hypothesis. He poses an important question: Why do criminals who loot tonnes of wealth remain poor, while there are people in society who have successfully accumulated enormous amounts of wealth and property with no ostensible source of income?

And, he goes on to narrate an incident where a dacoity took place in a small town of Bihar and police were able to nab the culprits in time, however only a small part of the loot was recovered. While the media was focused on the arrest of criminals and timely solving of the case, the author was concerned as to what happened to the larger part of the loot that police could not recover. And, in this missing link Abhayanand traces the anatomy of organised crime.

He writes, “I kept looking in the hope to find answers to these nagging questions. As years rolled by and as I gained more experience, I was able to observe some connection between this missing share of the loot and the ill-gotten wealth in the society. The shape and form would change, but the source essentially remained the same. The blue-collared criminals would graduate into white-collared ones.”

As a police officer who had a knack of a social scientist in understanding social issues, Abhayanand knew that if these crimes had to be checked, the need was to block the channels that would help this looted money to be mainstreamed and made part of the economy. Once the channel is blocked and these criminals find no resource to channel this money, the entire purpose behind these crimes would be rendered useless.

In a popular narrative, Bihar is a state which is marked by lawlessness — defined in terms of crimes like kidnapping and murders which dissuades investors from investing in the state which in turn leads to the perpetuation of backwardness, underdevelopment which has cyclic repercussions in form of lack of employment opportunities and unemployment which is thought to be significant propeller of criminal activities.

But this oversimplification finds a strong and convincing rebuttal from the author. During a freewheeling and insightful conversation with me, he provided an alternative and convincing explanation.

He narrates an interesting incident. When he was serving as Additional Director General of Police (ADG), a group of Non-resident Indians (NRI) from the United States had come to meet the chief minister with an intent to invest in the state and Abhayanad was asked to sit with them and look into their concerns.

“It was a day long meeting. Finally, what they said surprised me. They said, ‘ADG Sahab, do you think that we are worried about the kidnappings and murders that take place in the state.’ I said, ‘I think you are.’ They said, ‘No, we will be investing more money than your government will. I will be coming once a year just to see whether my money is safe or not. We will be staying in the best hotels in Patna where we will be ensured full safety. So, we are not afraid of being kidnapped. We are concerned about our money. The stories of defalcation, cheating and swindling of money are what worry us. Because we are going to invest our money here and we just want a guarantee of it being safe’,” says Abhayanand.

The next day when the chief minister inquired about the meeting what Abhayanand told is a strong case in point and worth quoting here as it makes it evident that the reason behind the lack of investment that Bihar has been complaining about for decades lies somewhere else rather than where it is usually thought to be present.

“I told the Chief Minister that we have land in the village, which I hardly find time to go and see. There are people looking after my land, I am concerned that nobody takes away the produce of the land and the land remains safe. Similarly, what they (the investors) are looking for and essentially want is ‘Braahil’ (a colloquial term for caretakers in Bihar) who can assure them the safety of their money.

The fact remains that Bihar has witnessed numerous financial scams and cases of siphoning off thousands of crores of public money by political-bureaucratic nexus often defined as ‘ghotala’. The fact remains that in the past a sitting chief minister was accused of and later convicted for embezzlement of hundreds of crores of public money.

The fact remains that such scams have been a regular headline-making feature of Bihar’s economy and politics. From the very infamous flood relief scam where the poster-boy of the civil services Gautam Goswami was accused of embezzlement for flood relief funds, the ‘ghotalas continue to make headlines in Bihar with the recent one being the Srijan scam where hundreds of crores of government funds were illegally transferred to an NGO working for women’s development.

“Crime is an economic activity, it’s not for fun except for a few passion crimes. DGP goes after a system, not individuals, exploring the reason behind the crime. Getting to the roots of the crime is the job of a police head and that is exactly what I did and tried to strike at the root cause,” says Abhayanand.

During his policing career he made several landmark changes in the way policing was done in Bihar. From streamlining and strengthening the scientific investigation by shifting the focus from ‘Bayan’ to ‘Vigyaan’ to unleashing a systematic attack “against all hues and colours of gangs operating across Bihar” with the help of the Enforcement Directorate (ED).

Remaining apolitical in a state like Bihar where politics runs through its social-cultural capillaries is an extremely tough task. It becomes even tougher for a police officer as crime finds systematic patronage of politics here. But, Abhayanand did this with an earnest and charming simplicity.

He writes in a chapter, ‘O Captain! My Captain’ how when he was told that he was going to be the next DGP of the state in August 2011 and went to meet the Chief Minister, he just made one request that he should be told frankly when he becomes a “political liability”, he would then file in his papers and quit.

In his three-year tenure as state police chief, Abhayanand did his most to write off the real liabilities of the state like organised crime syndicates, mafias, and bahubalis. In course of this he could have become a liability for certain people, but remained and will remain an asset to the people of Bihar, for he made a real attempt to bring a positive change for his land and the people.

Abhayanand’s memoir has ‘unbounded’ offerings for all: Police officials, bureaucrats, lawmakers, civil service aspirants, and management students. The memoir is full of rich anecdotes from a policing career spanning around four decades and notes from a teaching ‘mission’ that goes on. It is an account of an ‘Unbounded’ and unfettered resolve to bring in positive change and that is what makes it an engaging and inspiring read.

Abhayanand is the author of book ‘Unbounded: My Experiments with Law, Physics, Policing and Super 30’ (Rupa publications, Rs 595)

The interviewer is a journalist and researcher based in Delhi. He has worked with The Indian Express, Firstpost, Governance Now, and Indic Collective. He writes on Law, Governance and Politics. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

from Firstpost India Latest News https://ift.tt/e5uRLMN

0 Comments