Recently, a news report that created quite a stir was the Goa government’s decision to undertake the restoration of temples destroyed during Portuguese rule. The chief minister while speaking to the press said that a survey of temples and temple ruins has been started by the State Archives and Archaeology department, which is a part of the temple restoration project. It is a welcome declaration by the state government, as it is a long forgotten and rarely discussed topic in Goa.

The very name Goa conjures up scenes of sea, sand, and beaches; lush monsoon greenery; seasonal waterfalls; and the various churches built by the Portuguese. Archaeological findings from this small state, which include inscription plates, pottery fragments, sculptures, and remnants of ancient structures, provide valuable insights into the life of a common man and speak of thriving foreign trade and a vibrant trade-based economy in ancient and medieval Goa. These artifacts also speak of a Goa that was once filled with Hindu temples, now almost all gone with churches built in their places by the Portuguese.

A Hindu history of Goa

Goa’s history goes long back into the prehistoric era as evident from the various archaeological yields showing Acheulean occupation (lower Paleolithic era) in the Shimoga-Goa Greenstone Belt (Western Ghats). Rock art engravings (petroglyphs) on laterite platforms and granite boulders have been found in Usgalimal near the Kushavati river, and in Kajur. Stone-axes, choppers, and petroglyphs, dating back to 10,000 years have been found in many places in Goa. Archaeological evidences of Paleolithic life have been found at Maulinguinim, Dabolim, Arli, Adkon, Diwar, Shigao, Fatorpa, etc.

Historically documented records of Goa go back to 3rd BCE when Chandragupta Maurya reigned supreme. Some excavated pottery found in Chandrapur belonging to the Satavahanas show the presence of this ruling dynasty and place the probable origin of this once important trade centre to 200 BCE. After the Satavahanas, came the Bhojas who made Chandrapur (now Chandor) their capital, as evident from the various inscriptions found, dated between 3rd and 4th centuries CE. Next in line to rule Goa were the Chalukyas of Badami, followed by the Shilaharas, and lastly the Kadambas. As maritime supremacy reached its zenith under the Kadambas, the area known to the Arab cartographers as Zindabar, thrived as a central hub for various commercial activities. Both Hinduism and Jainism flourished under the Kadambas.

During the rule of the Chalukyas (600-700 CE) and Shilaharas (800-1000 CE), Gopakapattana (modern Velha Goa) was made the new capital of Goa, replacing the ancient Bhoja capital city of Chandrapura (modern Chandor, in Salcette). From the archaeological remains and various Sanskrit inscriptions it is evident that Gopakapattana had a Shiva temple that also housed a local god named Govanātha or Goveśvara. The Kadamba rule (1000-1400 CE) saw a strong revival of the local Hindu culture, and during this time period many temples were built in the heartland of Goa. There are many evidences that the Kadamba rulers had adopted the local deity Saptakotīśvara as their kuldevta, and built a large temple in basalt stone for him on the island of Diwar (Tiswadi).

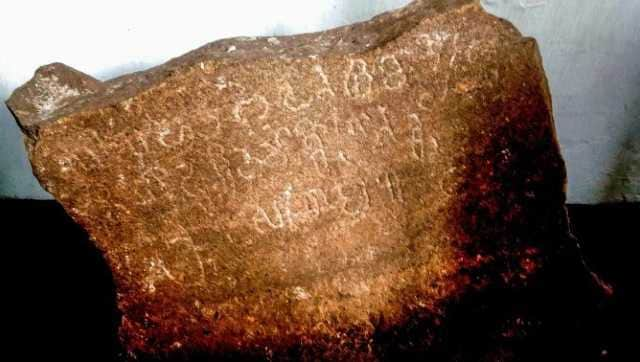

Epigraphic and textual sources documenting the early Hindu culture of Goa are found in copper and stone plate inscriptions written in in Sanskrit, Kannada, and Marathi; along with various Māhātmyas and the Purānas, which are variously dated from 5th to 13th century CE. The most famous among the Puranas that has documented the Hindu history of Goa is the Sahyādrikhanda of the Skandapurāna.

The most important story in the Sahyādrikhanda is that of the migration of the Saraswat branch of the Pancha Gauda Brahmins from north-east India to Goa. It gives a detailed account of the 66 Gauda Saraswat Brahmin families whom Parasurāma brought from Trihotra (modern Tirhut in West Bengal), and settled them in eight Goan villages Varenya (Verem), Kelosi (Quelossim), Kuśasthala (Cortalim), Kudasthali (Curtorim), Mathagrāma (Madgaon), Lotali (Loutulim), and two islands in the Mandovi River: Dipāvati (Diwar) and Cūdamani (Chorao). Various passages in the Sahyādrikhanda and also in the Mangeśamāhātmya (Skandapurāna) refer to deities that the Gauda Saraswat Brahmins had brought with them to Goa. These are Śantadurgā, Mahālaksmī, Mangeśa, Saptakotīśvara, and Nageśa, all of whom are still widely worshipped in various temples in Goa even today.

There are, however, other versions of the same story that talk of the Gauda Saraswat Brahmins in Goa not coming from Bengal but from the region around the ancient river Sarasvatī in north India; while a few modern scholars also claim of local priests who later named themselves as Gauda Saraswat Brahmins. There are also debates on the same topic between the Konkani-speaking Gauda Saraswat Brahmins and the Marathi-speaking Deshastha and Kharhade Brahmans living in Goa.

Among the aforementioned ancient deities, the most widely worshipped Devi in Goa even today is Śāntādurgā, also known as Bhumika or Saterī, worshipped not only by the Gauda Saraswat Brahmans, but also by the Marathas and tribal communities, namely Kunbi and Gavda. Another popular deity is Devi Mahālaksmī, whose worship has been documented from the reign period of the Shilaharas and Kadambas in the Sahyādrikhanda. Kelbai, also known as GajaLakshmi or Bhaukadevī, is another figure of veneration, as is Mhālsā Devī. Devi Kāmāksī, another Devi worshipped widely, is most likely an imported figure from Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu.

Mhālsā Devī and Devi Kāmāksī both are popular kuladevīs in villages, a characteristic of Goan goddesses who all are intricately associated with their localities. Among the male deities Nagesa, Saptakotisvara, and Mangesa (all forms of Shiva) are old Goan gods, and all three find mentions in the various Puranas, and also in the copper and stone plate inscriptions from the Kadamba period. The major Vaishnava deities worshipped by the Gauda Saraswat Brahmins and Marathas are Vitthal, Laksmī-Nārāyana, Damodāra, Ramachandra, Parasurama, Krishna, Narasimha, and Maruti.

The brutal invasions

The peace and prosperity under the Kadamba dynasty was shattered with the appearance of Malik Kafur and his invading Islamic army in the horizon like black locusts in 1312 CE. Soon the entire Konkan region along with Goa faced massive destruction at the hands of this general of the Delhi Sultanate. In order to escape Malik Kafur, the Kadamba king moved to the erstwhile capital of Chandor, and built a fort there. When Kafur came in 1312, the Kadambas were already a spent force, and their kingdom was limited to just Goa.

Additionally, the dynasty had started facing trouble with internal fights over the control of power. The thriving trade by this time had also dwindled considerably due to various factors, both external and internal. Whatever was left of the Kadambas, was completely destroyed by Muhammad bin Tughlaq’s Islamic army in 1327 CE. After this, Goa briefly went under the Vijayanagara empire, followed by the Bahmani Sultans (1469 CE), and lastly the Adil Shahis of Bijapur (1488 CE). The power race of the Islamic invading armies finally ended here, and in came a new player from across the western seas, the Portuguese!

The Portuguese came to power in Goa in 1510, after defeating the Bijapur Sultan, Yousuf Adil Shah. They set up their first capital in Velha Goa and thus began their four century long rule in the state. At this time, they imposed their infamous ‘Inquisition’ on the people of Goa, with the objective of forcibly converting local Hindus to Roman Catholics. This Inquisition was primarily a method of social control against the Hindus and the converted Catholics, who they feared, practised their old faith behind closed doors. Later, it was also imposed on the Jews from Portugal, along with some of the old Christians and new converts too. Soon this turned into an easy way of taking away desirable properties by the Inquisitors.

The infamous brutal Goa Inquisition was started when the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier in a letter dated 16 May 1546 requested for it to King John III of Portugal. Between the Inquisition’s start in 1561 and a temporary stop in 1774, it is believed that more than 16,000 non-Catholics (mainly Hindus) were brought to trial. As the French historian and philosopher Voltaire tells us, “Goa is sadly famous for its Inquisition, which is contrary to humanity as much as to commerce. The Portuguese monks deluded us into believing that the Indian populace was worshipping the Devil, while it is they who served him” (ref: Lettres sur l’origine des sciences et sur celle des peuples de l’Asie; first published Paris, 1777, letter of 15 December 1775). In the first few years of the inquisition more than 4,000 people were arrested, and 121 were burnt alive at the stake.

Many anti-Hindu laws and prohibitions were passed by the Portuguese colonial government. For example, Christians were not allowed to keep Hindus as their employees and Hindus were not allowed to perform any form of public worship. Many restraining religious laws were also passed, which included a ban on Hindu musical instruments and clothing. Majority of the Hindu temples were destroyed or converted into churches, and often materials from the destroyed temples were used to build these churches. During the entire inquisition period many important Hindu texts were burned, and Christian religious texts were forcibly imposed on the Hindus.

Under orders by the viceroy of Goa, Antao de Noronha and Governor Antonio Moniz Barrette, orphan Hindu children were ordered to be “taken immediately and handed over to the College of St Paul of the society of Jesus of the said city of Goa, for being baptised, educated and indoctrinated by the Fathers of the said College and being directed by them and placed in positions according to their respective aptitudes and abilities”. Besides orphans, often Hindu children with parents were kidnapped and forcibly converted, and such was the level of torture that many Hindu families smuggled their children out of Goa, while others paid extortion money to Christian priests to prevent conversions.

Many families facing the brutalities of these Inquisitors converted to Christianity to save their lives, and some of these early converts were richly rewarded. The first family to embrace Christianity in the ancient capital of the Bhojas, Chandrapur (Chandor), was the Braganza family. They were granted trade rights to various parts of the world, as a result of which the family became immensely wealthy within a short span and built a huge mansion that is one of the largest and the oldest surviving Portuguese villas in Goa. The opulent interiors still reflect the long gone grandeur of these palatial homes, and while moving from one room to another one can only imagine the immense wealth and power that these families had once enjoyed after conversion.

Owing to the brutal nature of the Goan Inquisition there was a large-scale migration of Hindus to the neighbouring areas, and this situation continued in Goa until the 19th century. While the Goa Inquisition details (of arrests, trials, deaths, etc) were carefully recorded by the Portuguese government, most of these records are now lost, as they were burned by the Portuguese when they abolished the Inquisition in 1820.

The author is a well-known travel and heritage writer. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

from Firstpost India Latest News https://ift.tt/GDcIkXl

0 Comments